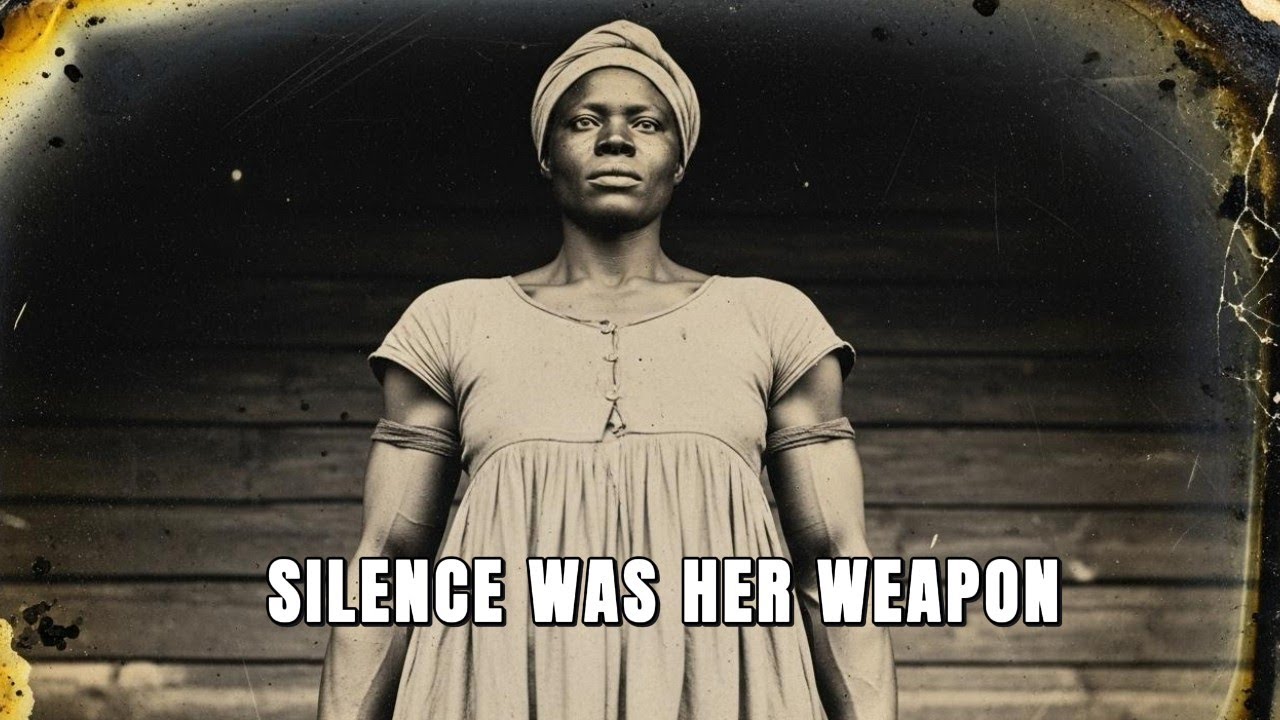

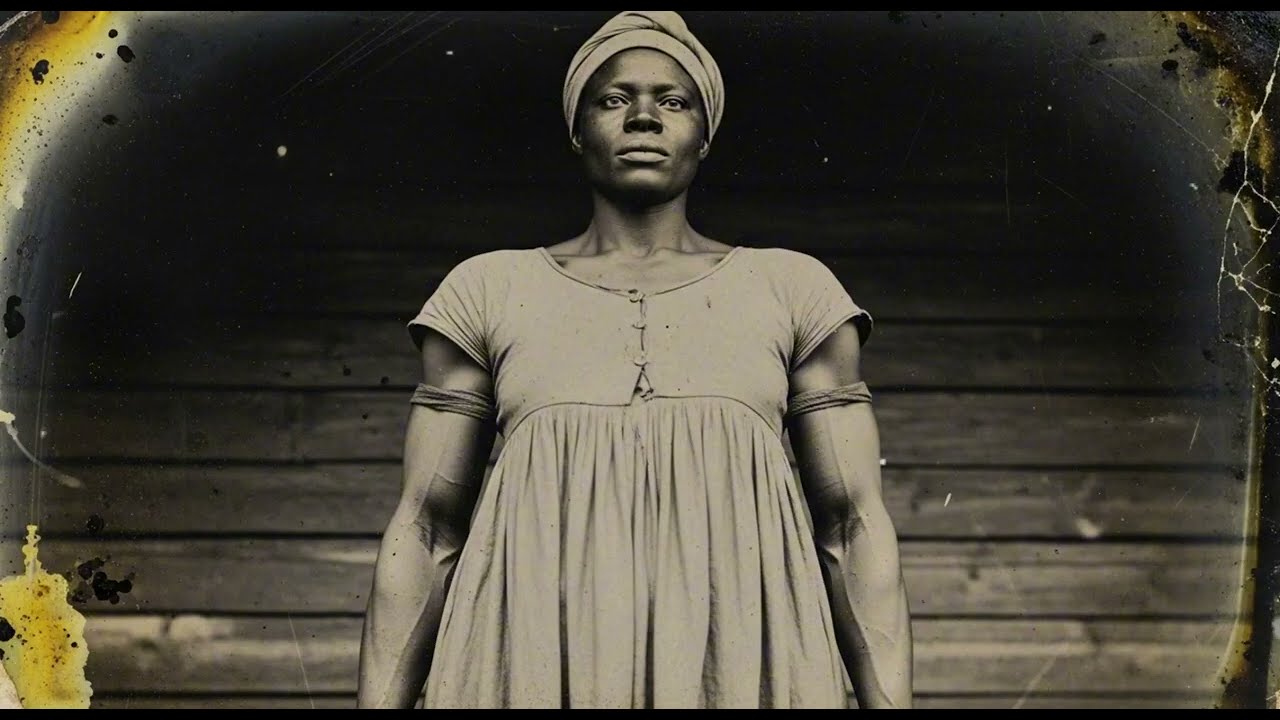

The Giant sʟᴀᴠᴇ Woman Never Spoke… Until She Whispered What Master Did to Her 9 Daughters .m

By the time the flames reached the courthouse roof, no one thought they were destroying anything more than dusty ledgers and Confederate files. But hidden among the ashes of the 1865 Henrico County Courthouse fire, a clerk named Josiah Peton claimed something else had burned—twenty-three pages of testimony so disturbing that the Reconstruction authorities ordered every copy destroyed.

The testimony belonged to a woman known only by a name whispered in horror and reverence across Virginia’s plantations: Big Sarah, the Silent Giant.

The Arrival at Greenbryer

In the summer of 1831, as Nat Turner’s rebellion ignited fear across the South, a towering slave woman arrived at Greenbryer Plantation in Powhatan County, Virginia. She was six feet seven inches tall, with shoulders broad enough to carry the weight of any man’s cruelty. Her name, according to the trader who sold her for $800, was Sarah.

She did not speak. Not a word. The trader, Vernon Caldwell, warned that she had been silent for years—since witnessing something unspeakable happen to her mother on a South Carolina plantation. From that day forward, he said, Sarah’s lips had sealed as though language itself had betrayed her.

To Nathaniel Crowther, the plantation owner who bought her, her silence was not a curse. It was an opportunity.

The Breeding Program

Crowther was a man of ambition wrapped in genteel cruelty. He called himself a modernizer, a “scientific planter.” He studied animal husbandry and applied those same principles to human beings. In the ledger he kept, he referred to his slaves not by name but by measurements: height, weight, reproductive capacity.

Sarah, he believed, was the foundation of a new generation—his “improved line.”

Her first child, a daughter named Delilah, was born during a thunderstorm in 1832. Sarah made no sound through the pain. The midwife, an elderly slave woman named Patience, later said that the silence in that cabin was more terrible than any scream. Crowther noted in his journal that Delilah was “a perfect specimen.”

Within fifteen years, Sarah bore him nine daughters. Each was tall, strong, and light-skinned. Each was recorded meticulously in Crowther’s journal as if she were a calf or foal. And each was taken from her mother as soon as she could walk.

Sarah remained silent through it all.

To the others at Greenbryer, that silence became legend—a kind of shield forged from unbearable grief. One woman later said, “She wasn’t quiet because she was broken. She was quiet because she was waiting.”

A House of Daughters

By 1836, the plantation’s cabins were filled with Sarah’s children. Crowther saw them as his legacy. “Daughters,” he once wrote, “are the true investment. They will breed the next generation.”

He raised them in isolation, trained them for domestic work, and kept them from their mother. The eldest, Delilah, grew into a striking young girl nearly six feet tall by the age of thirteen. When visitors came, Crowther introduced her as his ward.

The truth was an open secret.

The house slaves whispered that Crowther’s gaze lingered too long on his daughters. They saw how he “inspected” them. How the same patterns that had begun with Sarah were now repeating.

In his private journal, Crowther wrote of “continuing the line.”

It was not an entry about agriculture.

The Breaking Point

In November of 1837, Sarah broke her silence—though not yet with words.

That night, she appeared in Crowther’s study, holding a kitchen knife. He had been found with her five-year-old daughter, Delilah. What she saw was never recorded. What followed was.

Sarah struck him with a candlestick, cutting his forehead open. The overseer, Edmund Yancey, arrived to find Crowther bleeding and Sarah standing motionless, the knife still in her hand. When Crowther screamed for Yancey to shoot, the overseer hesitated. Sarah simply turned and walked away, returning to her cabin as if she were walking home from the fields.

By dawn, she had delivered another daughter—her ninth. Crowther, torn between rage and greed, refused to kill her. Instead, he chained her permanently inside her cabin, an iron collar bolted to the wall. He said she was “too valuable to destroy.”

For nine years, Sarah lived like that—silent, chained, used.

The Preacher and the Overseer

By the mid-1840s, Greenbryer had become infamous among neighboring plantations. Its owner no longer hid his breeding obsession. When a Methodist preacher named Reverend Sheffield visited to deliver sermons to the slaves, he noticed the unusual number of light-skinned girls working the house.

When he asked to meet their mother, Crowther refused. But that night, one of the older slaves, Bess, told the preacher enough to make his blood run cold. He left the next morning and wrote two letters—one to his bishop and one to a sympathetic minister in Richmond—warning that “a monstrous evil thrives under the name of husbandry in Powhatan County.”

Meanwhile, Edmund Yancey, the overseer, began keeping a secret journal. He wrote of Crowther’s “night visits,” of the daughters’ tears, of Rebecca’s failed escape and Delilah’s pregnancy at fourteen.

Even in the mind of a man who still believed in slavery, Crowther’s crimes had crossed a line that civilization could no longer explain.

The Awakening

In February of 1847, Yancey unlocked Sarah’s cabin door. For the first time in nearly a decade, she spoke.

“How long until spring?” she asked.

When Yancey told her two months, she nodded. Then she asked, “Where do they keep the keys?”

He told her the truth—behind Crowther’s desk. Sarah said only, “Go. Do not come back. When it happens, say you knew nothing.”

She had waited sixteen years for that conversation.

The Night of Fire and Water

On April 3rd, 1847, Crowther held a grand party at Greenbryer to showcase his “success.” The house glowed with candlelight and the laughter of planters who would later pretend they hadn’t known what kind of man their host was.

While dinner was being served, Sarah broke through the weakened wall of her cabin. She had twisted her chain into armor and a weapon. One by one, she freed her daughters from their locked rooms, her massive figure gliding through the corridors like an avenging ghost.

By the time Crowther noticed the silence in his kitchen, Sarah and all nine daughters were gone.

Dogs were released. Lanterns swept the fields. Search parties scoured the woods. But by dawn, they had vanished.

Three days later, Yancey found a sandbar on the James River. On it stood nine piles of stones, each topped with a small wooden cross. And in the water nearby, just her head above the current, was Sarah.

Their eyes met. She sank beneath the surface and did not rise again.

The Fall of Greenbryer

Crowther’s world collapsed faster than any mob could burn it down.

When word spread that nine enslaved women—all his own daughters—had escaped, the whispers became accusations. Planters who had once shaken his hand now crossed the street to avoid him.

His creditors called in debts. His papers were seized. And in those papers, investigators found the proof—the ledgers, the breeding records, the charts describing “stock improvement.”

Even in a world built on bondage, there were things too vile to defend.

Crowther sold Greenbryer for a fraction of its worth and moved to Richmond, where he died five years later, delirious and muttering about chains and rivers.

Echoes of the Missing

None of the nine daughters were ever recaptured.

Some claimed they drowned in the river. Others swore they reached freedom through the Underground Railroad. There are fragments—letters and census entries that hint they might have survived.

A Quaker minister in Pennsylvania wrote in 1848 about “a group of tall mulatto women who speak little and move like soldiers.” A Canadian schoolteacher described nine sisters who refused to talk about their past but built a farm near Lake Ontario.

And in a Michigan census two decades later, there appears a family headed by a woman named “Sarah D.” with eight sisters of nearly the same age. The handwriting is blurred by water, as if the record itself tried to remember through tears.

The Sandbar and the Silence

Greenbryer never recovered. The plantation changed hands repeatedly until the Civil War, when the house burned. Today, the land lies beneath pine and honeysuckle, quiet except for the wind that whispers across what used to be the fields.

But along the James River, about three miles away, there is a sandbar that reappears every summer when the water runs low. Visitors sometimes find small piles of stones there, arranged in groups of nine. Teenagers knock them over. By the next year, they return.

The Last Word

When Josiah Peton’s daughter donated his papers in 1908, archivists found one hidden scrap from the testimony that was supposed to have been destroyed. It contained Sarah’s answer when a Union officer asked why she had never spoken.

“Words are what they use to lie. I had no words left that were not stolen or twisted. So I saved my silence like a knife—sharp and clean—until the moment I could cut us free.”

For nearly two centuries, the story of the Silent Giant has been buried beneath polite history. But silence does not stay buried forever.

Somewhere between the river and the ruins, it still breathes—the sound of a woman who waited sixteen years to whisper the truth about what a master did to her nine daughters, and how she turned her silence into deliverance.